John Updike died today.

I love the novels of his that I've read (all the "Rabbit" books, "Witches of Eastwick," "Couples," "S.") and plan to read the others. Sorry never to have met him or heard him speak, despite the fact that he is native to Shillington, about 30 minutes from here.

What an imagination!

(I blogged about and posted an article about his most recent book, The Widows of Eastwick, in November 2008. You can check that out by clicking here.)

Date: 1/27/2009 2:36 PM

John Updike, prize-winning writer, dead at age 76

John Updike, prize-winning writer, dead at age 76

By HILLEL ITALIE

AP National Writer

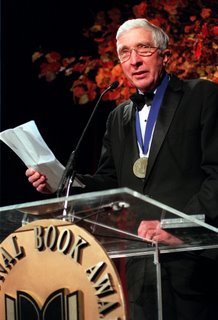

NEW YORK — John Updike, the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, prolific man of letters and erudite chronicler of sex, divorce and other adventures in the postwar prime of the American empire, died Tuesday at age 76.

Updike, best known for his four "Rabbit" novels, died of lung cancer at a hospice near his home in Beverly Farms, Mass., according to his longtime publisher, Alfred A. Knopf.

A literary writer who frequently appeared on best-seller lists, the tall, hawk-nosed Updike wrote novels, short stories, poems, criticism, the memoir "Self-Consciousness" and even a famous essay about baseball great Ted Williams.

He released more than 50 books in a career that started in the 1950s, winning virtually every literary prize, including two Pulitzers, for "Rabbit Is Rich" and "Rabbit at Rest," and two National Book Awards.

Although himself deprived of a Nobel, he did bestow it upon one of his fictional characters, Henry Bech, the womanizing, egotistical Jewish novelist who collected the literature prize in 1999.

His settings ranged from the court of "Hamlet" to postcolonial Africa, but his literary home was the American suburb, the great new territory of mid-century fiction.

Born in 1932, Updike spoke for millions of Depression-era readers raised by "penny-pinching parents," united by "the patriotic cohesion of World War II" and blessed by a "disproportionate share of the world's resources," the postwar, suburban boom of "idealistic careers and early marriages."

He captured, and sometimes embodied, a generation's confusion over the civil rights and women's movements, and opposition to the Vietnam War. Updike was called a misogynist, a racist and an apologist for the establishment. On purely literary grounds, he was attacked by Norman Mailer as the kind of author appreciated by readers who knew nothing about writing. Last year, judges of Britain's Bad Sex in Fiction Prize voted Updike lifetime achievement honors.

But more often he was praised for his flowing, poetic writing style. Describing a man's interrupted quest to make love, Updike likened it "to a small angel to which all afternoon tiny lead weights are attached."

Nothing was too great or too small for Updike to poeticize. He might rhapsodize over the film projector's "chuckling whir" or look to the stars and observe that "the universe is perfectly transparent: we exist as flaws in ancient glass."

In the richest detail, his books recorded the extremes of earthly desire and spiritual zealotry, whether the comic philandering of the preacher in "A Month of Sundays" or the steady rage of the young Muslim in "Terrorist." Raised in the Protestant community of Shillington, Pa., where the Lord's Prayer was recited daily at school, Updike was a lifelong churchgoer influenced by his faith, but not immune to doubts.

"I remember the times when I was wrestling with these issues that I would feel crushed. I was crushed by the purely materialistic, atheistic account of the universe," Updike told The Associated Press during a 2006 interview.

"I am very prone to accept all that the scientists tell us, the truth of it, the authority of the efforts of all the men and woman spent trying to understand more about atoms and molecules. But I can't quite make the leap of unfaith, as it were, and say, 'This is it. Carpe diem (seize the day), and tough luck.'"

He received his greatest acclaim for the "Rabbit" series, a quartet of novels published over a 30-year span that featured ex-high school basketball star Harry "Rabbit" Angstrom and his restless adjustment to adulthood and the constraints of work and family. To the very end, Harry was in motion, an innocent in his belief that any door could be opened, a believer in God even as he bedded women other than his wife.

The series "to me is the tale of a life, a life led by an American citizen who shares the national passion for youth, freedom, and sex, the national openness and willingness to learn, the national habit of improvisation," Updike would later write. "He is furthermore a Protestant, haunted by a God whose manifestations are elusive, yet all-important."

Other notable books included "Couples," a sexually explicit tale of suburban mating that sold millions of copies; "In the Beauty of the Lilies," an epic of American faith and fantasy; and "Too Far to Go," which followed the courtship, marriage and divorce of the Maples, a suburban couple with parallels to Updike's own first marriage.

Updike's "The Witches of Eastwick," released in 1984, was later made into a film of the same name starring Jack Nicholson, Cher, Michelle Pfeiffer and Susan Sarandon.

Plagued from an early age by asthma, psoriasis and a stammer, he found creative outlets in drawing and writing. Updike was born in Reading, Pa., his mother a department store worker who longed to write, his father a high school teacher remembered with sadness and affection in "The Centaur," a novel published in 1964. The author brooded over his father's low pay and mocking students, but also wrote of a childhood of "warm and action-packed houses that accommodated the presence of a stranger, my strange ambition to be glamorous."

For Updike, the high life meant books, such as the volumes of P.G. Wodehouse and Robert Benchley he borrowed from the library as a child, or, as he later recalled, the "chastely severe, time-honored classics" he read in his dorm room at Harvard University, leaning back in his "wooden Harvard chair," cigarette in hand.

While studying on full scholarship at Harvard, he headed the staff of the Harvard Lampoon and met the woman who became his first wife, Mary Entwistle Pennington, whom he married in June 1953, a year before he earned his A.B. degree summa cum laude. (Updike divorced Pennington in 1975 and was remarried two years later, to Martha Bernhard).

After graduating, he accepted a one-year fellowship to study painting at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Arts at Oxford University. During his stay in England, a literary idol, E.B. White, offered him a position at The New Yorker, where he served briefly as foreign books reviewer. Many of Updike's reviews and short stories were published in The New Yorker, often edited by White's stepson, Roger Angell.

By the end of the 1950s, Updike had published a story collection, a book of poetry and his first novel, "The Poorhouse Fair," soon followed by the first of the Rabbit books, "Rabbit, Run." Praise came so early and so often that New York Times critic Arthur Mizener worried that Updike's "natural talent" was exposing him "from an early age to a great deal of head-turning praise."

Updike learned to write about everyday life by, in part, living it. In 1957, he left New York, with its "cultural hassle" and melting pot of "agents and wisenheimers," and settled with his first wife and four kids in Ipswich, Mass, a "rather out-of-the-way town" about 30 miles north of Boston.

"The real America seemed to me 'out there,' too heterogeneous and electrified by now to pose much threat of the provinciality that people used to come to New York to escape," Updike later wrote.

"There were also practical attractions: free parking for my car, public education for my children, a beach to tan my skin on, a church to attend without seeming too strange."

In recent years, his books included "The Widows of Eastwick," a sequel to "The Witches of Eastwick"; and two essay collections, "Still Looking" and "Due Considerations." A book of short fiction, "My Father's Tears and Other Stories," is scheduled to come out later this year.

Updike is survived by his second wife, Marsha, and by four children.

NEW YORK — John Updike, the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, prolific man of letters and erudite chronicler of sex, divorce and other adventures in the postwar prime of the American empire, died Tuesday at age 76.

Updike, best known for his four "Rabbit" novels, died of lung cancer at a hospice near his home in Beverly Farms, Mass., according to his longtime publisher, Alfred A. Knopf.

A literary writer who frequently appeared on best-seller lists, the tall, hawk-nosed Updike wrote novels, short stories, poems, criticism, the memoir "Self-Consciousness" and even a famous essay about baseball great Ted Williams.

He released more than 50 books in a career that started in the 1950s, winning virtually every literary prize, including two Pulitzers, for "Rabbit Is Rich" and "Rabbit at Rest," and two National Book Awards.

Although himself deprived of a Nobel, he did bestow it upon one of his fictional characters, Henry Bech, the womanizing, egotistical Jewish novelist who collected the literature prize in 1999.

His settings ranged from the court of "Hamlet" to postcolonial Africa, but his literary home was the American suburb, the great new territory of mid-century fiction.

Born in 1932, Updike spoke for millions of Depression-era readers raised by "penny-pinching parents," united by "the patriotic cohesion of World War II" and blessed by a "disproportionate share of the world's resources," the postwar, suburban boom of "idealistic careers and early marriages."

He captured, and sometimes embodied, a generation's confusion over the civil rights and women's movements, and opposition to the Vietnam War. Updike was called a misogynist, a racist and an apologist for the establishment. On purely literary grounds, he was attacked by Norman Mailer as the kind of author appreciated by readers who knew nothing about writing. Last year, judges of Britain's Bad Sex in Fiction Prize voted Updike lifetime achievement honors.

But more often he was praised for his flowing, poetic writing style. Describing a man's interrupted quest to make love, Updike likened it "to a small angel to which all afternoon tiny lead weights are attached."

Nothing was too great or too small for Updike to poeticize. He might rhapsodize over the film projector's "chuckling whir" or look to the stars and observe that "the universe is perfectly transparent: we exist as flaws in ancient glass."

In the richest detail, his books recorded the extremes of earthly desire and spiritual zealotry, whether the comic philandering of the preacher in "A Month of Sundays" or the steady rage of the young Muslim in "Terrorist." Raised in the Protestant community of Shillington, Pa., where the Lord's Prayer was recited daily at school, Updike was a lifelong churchgoer influenced by his faith, but not immune to doubts.

"I remember the times when I was wrestling with these issues that I would feel crushed. I was crushed by the purely materialistic, atheistic account of the universe," Updike told The Associated Press during a 2006 interview.

"I am very prone to accept all that the scientists tell us, the truth of it, the authority of the efforts of all the men and woman spent trying to understand more about atoms and molecules. But I can't quite make the leap of unfaith, as it were, and say, 'This is it. Carpe diem (seize the day), and tough luck.'"

He received his greatest acclaim for the "Rabbit" series, a quartet of novels published over a 30-year span that featured ex-high school basketball star Harry "Rabbit" Angstrom and his restless adjustment to adulthood and the constraints of work and family. To the very end, Harry was in motion, an innocent in his belief that any door could be opened, a believer in God even as he bedded women other than his wife.

The series "to me is the tale of a life, a life led by an American citizen who shares the national passion for youth, freedom, and sex, the national openness and willingness to learn, the national habit of improvisation," Updike would later write. "He is furthermore a Protestant, haunted by a God whose manifestations are elusive, yet all-important."

Other notable books included "Couples," a sexually explicit tale of suburban mating that sold millions of copies; "In the Beauty of the Lilies," an epic of American faith and fantasy; and "Too Far to Go," which followed the courtship, marriage and divorce of the Maples, a suburban couple with parallels to Updike's own first marriage.

Updike's "The Witches of Eastwick," released in 1984, was later made into a film of the same name starring Jack Nicholson, Cher, Michelle Pfeiffer and Susan Sarandon.

Plagued from an early age by asthma, psoriasis and a stammer, he found creative outlets in drawing and writing. Updike was born in Reading, Pa., his mother a department store worker who longed to write, his father a high school teacher remembered with sadness and affection in "The Centaur," a novel published in 1964. The author brooded over his father's low pay and mocking students, but also wrote of a childhood of "warm and action-packed houses that accommodated the presence of a stranger, my strange ambition to be glamorous."

For Updike, the high life meant books, such as the volumes of P.G. Wodehouse and Robert Benchley he borrowed from the library as a child, or, as he later recalled, the "chastely severe, time-honored classics" he read in his dorm room at Harvard University, leaning back in his "wooden Harvard chair," cigarette in hand.

While studying on full scholarship at Harvard, he headed the staff of the Harvard Lampoon and met the woman who became his first wife, Mary Entwistle Pennington, whom he married in June 1953, a year before he earned his A.B. degree summa cum laude. (Updike divorced Pennington in 1975 and was remarried two years later, to Martha Bernhard).

After graduating, he accepted a one-year fellowship to study painting at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Arts at Oxford University. During his stay in England, a literary idol, E.B. White, offered him a position at The New Yorker, where he served briefly as foreign books reviewer. Many of Updike's reviews and short stories were published in The New Yorker, often edited by White's stepson, Roger Angell.

By the end of the 1950s, Updike had published a story collection, a book of poetry and his first novel, "The Poorhouse Fair," soon followed by the first of the Rabbit books, "Rabbit, Run." Praise came so early and so often that New York Times critic Arthur Mizener worried that Updike's "natural talent" was exposing him "from an early age to a great deal of head-turning praise."

Updike learned to write about everyday life by, in part, living it. In 1957, he left New York, with its "cultural hassle" and melting pot of "agents and wisenheimers," and settled with his first wife and four kids in Ipswich, Mass, a "rather out-of-the-way town" about 30 miles north of Boston.

"The real America seemed to me 'out there,' too heterogeneous and electrified by now to pose much threat of the provinciality that people used to come to New York to escape," Updike later wrote.

"There were also practical attractions: free parking for my car, public education for my children, a beach to tan my skin on, a church to attend without seeming too strange."

In recent years, his books included "The Widows of Eastwick," a sequel to "The Witches of Eastwick"; and two essay collections, "Still Looking" and "Due Considerations." A book of short fiction, "My Father's Tears and Other Stories," is scheduled to come out later this year.

Updike is survived by his second wife, Marsha, and by four children.